In 1990, General Magic spun out of Apple to create a pocketable personal computer.

I spoke with Dee Gardetti and Michael Stern, two early employees, in 2019. Finally published in 2025.

I also highly recommend the General Magic documentary and Valley of Genius.

Background

It was a long and winding road. When I got out of college at Columbia, I started as a newspaper reporter at the Washington Post. I ended up getting a fellowship to go to Cambridge. The problem with graduate school is it socializes you into being an academic, so I ended up as an English professor. I taught at Yale and then one of the Cornell colleges.

My wife was very ill and needed to be treated at Stanford—it was the only place that had an experimental protocol that might work for her. So we just left Cornell and came to Palo Alto, and I've been here ever since.

I quit teaching eventually. There were so many interesting people around here. Our kids were in daycare at the Jewish center with all these folks who were starting companies, and they all seemed really interesting. They were all clients of a law firm whose partners also had kids in this daycare. Remember those old New York Times ads—"I got my job from the New York Times"? Well, I got my job through the Palo Alto Jewish Center.

I went to work at that law firm and became a partner. We were the firm that did everything on the other side of Apple—Apple used Wilson, the other big law firm in town, and we were always on the other side. Alan Eisenstat, the GC, contacted my boss and asked if we'd do this weird little project they had, which was spinning out this crazy little company. It turned out to be General Magic.

For a while it was so intense, I wasn't doing anything else anyway, so I just decided to go over and join it full-time. About a year after it was founded, I joined as the general counsel and stayed on.

I started there because I was Bill Atkinson's personal assistant pre-General Magic, and I had been working for him for a couple of years out of his home. That was right after he launched HyperCard. When Marc Porat approached them to be a co-founder at General Magic, I was basically in the right place at the right time.

It was great working with Bill. He's a wonderful human being—a very, very talented engineer and very kind.

Starting Out

At first it was just me, Bill, Andy Hertzfeld, and Marc. I ended up being head of HR because there was no one else there to do it. At the very beginning, it was basically me and the engineers. I not only did HR, but also payroll, benefits, executive assistance, and facilities. I did a lot of things depending on the day and what was needed. I did that for maybe a year until we started growing where obviously I couldn't handle it all, and then we would hire people to take things off my plate.

The reason I fell into HR is because I had some HR experience working at Hewlett-Packard. I was there for 15 years in the HR environment with very different people—mechanical engineers. It was a very different set of skills, but I learned a lot from working with those engineers at Hewlett-Packard. It made sense for me to do the work because at first it was just me, Bill, Andy, and Marc.

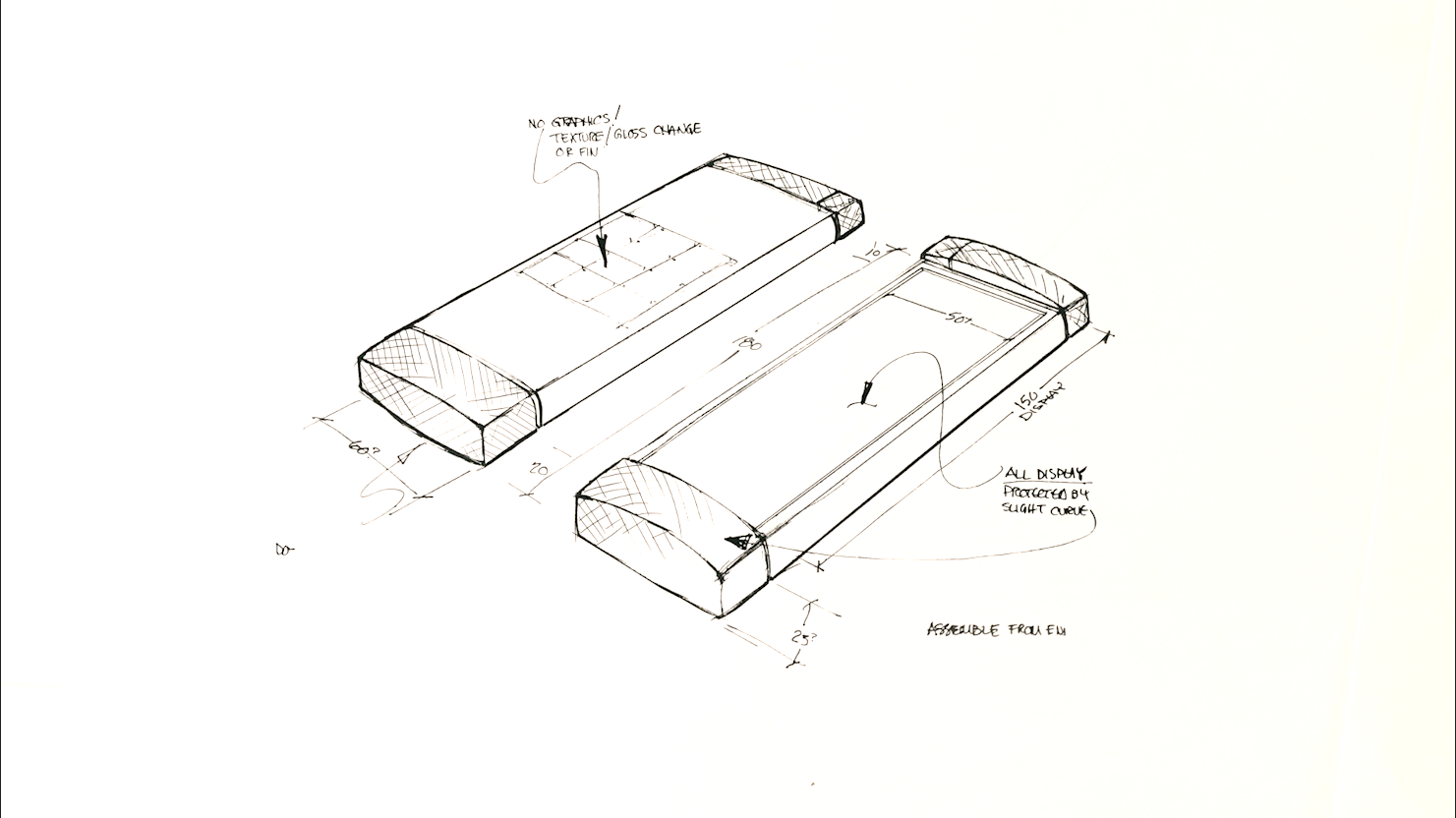

Marc had the book that he plays with in the movie—I have a copy. It was incredibly compelling. It really was the basis for what we now take for granted. It wasn't just the device; it was the idea of a service, the whole idea of a gateway to content and culture and personal interaction and commerce and the whole ecosystem around a portable device that could do many things. He had seen all that, written it up, drawn it. It was there.

It was like, roll up your sleeves and get in. Marc was focused on getting funding and running the company. Bill and Andy were focused on creating the product and developing an engineering team. A lot of the focus at the very beginning was hiring people.

It's true with all startups like that. You just do whatever needs to be done. I've always said with every startup, I eventually work myself out of a job because, especially if it grows, you need an accounting team, you need a facilities person, you need payroll and benefits specialists. I pretty much always worked myself out of a job but was always fortunate to find a niche.

Working Together

The partnership between Marc, Bill, and Andy was sometimes strained at first because Marc was the sales guy, not a technical guy. But Andy and Bill came to respect his overall technical vision about what the device should be and what the service should look like over time. After the first few months, they really worked well together.

Again, greatest strengths, greatest weaknesses. He let them do their thing. They supported him in building the partner alliance and raising the money. That division of labor worked pretty well.

The dynamic of building the team and working with them was always fun. Sometimes a little crazy. Sometimes I had no idea what I was doing, and it just kind of built from there. It was an experience I've never had again in any company I've worked for.

Culture

What was unique about it was the people and the talent of the people. It was really the only company I ever felt like we all had one goal in mind, and that was to develop this product that had never been developed before. There was never any confusion about what we were trying to do. It was just really hard to do it because it had never been done before. There's just no other team like it.

It was unusual at that time in the Valley. It was far more diverse than most places. We had senior women, women on the executive staff, a lot of women engineers. It was a really open, freewheeling place. Not a lot of hierarchy.

That was our greatest strength—it's what attracted people. It was also, as you could tell from the movie, our greatest weakness. No management, right? Marc was a visionary and he was out selling to the outside world, and the engineers kind of ran the store themselves. That's not a very good strategy for actually shipping a product. But it was incredibly intense, incredibly fun.

I'm sure that Apple and the Steve Jobs team was probably very similar when it first started. Of course, we had a good number of people from Apple join us, which we eventually got in trouble for. We were asked to stop recruiting people from Apple.

Hiring

That wasn't hard in the first year or two because we didn't really have to look hard—we had people coming to us. Bill and Andy brought many of the people they knew, and then those people would bring people that they knew.

Our first engineer that we hired, other than Bill and Andy who were founders, was Phil Goldman. He was an extraordinary person and engineer. Phil was such an incredible mentor and boss that people would follow him wherever he went. When Phil hired other people from Apple, eventually we got a call from Apple saying we had to stop hiring people from Apple.

We were taking their top engineers while they were working on the Newton. People are free to do what they want—we just couldn't actively ask people to join us. If they came to us, that would be different. But we couldn't recruit. We were asked to stop recruiting from Apple, which of course we did. That was an interesting time.

It was a 50-50 split. Most of the Mac 17 came over—people with proven track records that Bill and Andy had worked with. They had been around Apple and earned their chops.

The kids were just really impressive—the way they interviewed and their persistence. Tony Fadell really did sleep on the doorstep waiting around to get in. People would do all sorts of things to get an interview. The more ingenuity they displayed, the more promising they seemed.

Most of the first hundred people were either recruited by people already at General Magic or came to us. Back in the day, you couldn't really post anything online—it was pre-internet. We might have done a newspaper ad—tell you the truth, I can't even remember.

Like Tony said in the film, he was in Detroit and would read about us in Wired magazine. A lot of people heard about us that way and would just come to us, so it wasn't hard.

Interviews

We were so short-handed. I interviewed engineers—which you shouldn't have a corporate lawyer do. But you could just see the spark in people.

We didn't do "can you pass the test" kind of interviews, at least I didn't. People weren't given coding problems to solve. The stronger the personality and the more committed they seemed to be to working on something they thought was cool, the better they seemed. Bill and Andy were tremendous draws. To work with them was something that young engineers dreamed of.

What was special about it was that ethos of only talent mattered. Nobody cared who you were or where you came from. It wasn't about credentials, it was about what you had done. That was Bill and Andy's key criteria for hiring somebody.

Zarko Draganic—he did something really outlandish to get hired, but I can't remember what it was.

Management

There was very little structure. Me coming from the very corporate background of Hewlett-Packard where it's very structured and lots of rules, going to a company that was unstructured—that was mostly just because of the ages of the people. These are brilliant people and you don't want to structure people like that because it kills their creativity.

That was what was so great about it. It shows in the film—they were just so excited to be there that they really didn't need formal structure. Darren talks about it in the film too about bringing in a manager. They didn't even want a manager. In retrospect, even Tony admits it now, you do need that, especially as the company grows. But back then they didn't want it at all. That was probably the biggest challenge for Darren Adler when he was asked to manage the group, because it was not well accepted.

For the first four or five years, there was very little structure. Then as the company realized they were not going to be able to build the product, and the Newton came out, they tried to refocus and restructure. That's when the structure started coming in, but it was just too late at that point for our product to go anywhere.

There were never any hard, fast rules. I don't even know if we ever did an HR handbook until we got a whole lot bigger. A human resource handbook would never have worked in that environment.

People

A challenge, but fun. I was so much older—I was 44 and literally had kids older than most of the employees there. My kids were in their mid-20s, about the same age as anybody we had hired there. So to me, they were—I would reflect a lot on different personalities.

What I learned from working at Hewlett-Packard with those engineers was: remember these people are really young and they're brilliant, and they need to be talked to very directly, but in a kind way. I was really the mom of the group.

Tony was a character, and there were times I would have to say, "Tony, we need to concentrate more or take it down a little bit," because he was also a real big jokester. Every personality is different, so you don't treat everybody the same. You treat every personality with what they can relate to. My secret is I would always treat people the way that person I was talking to could relate to. They're all different personalities. That seems to work for me.

Work and Play

I was in my late 30s; the kids doing the work were all in their early 20s. So there was a lot of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. We had marriages, relationships, children born in the company.

There were so many things Tony did. Catapulting potatoes through the second floor window of our building. Sneaking up on people and scaring them by jumping out of somebody's office going "Boo!" He did that a lot. He was quite a prankster.

Tony built this gigantic slingshot using one of the support pillars in the building—like one of those really thick rubber bands you use in physical therapy. He had no idea what its terminal velocity would be.

There was this thing like silly putty, but they called it gack—G-A-C-K. It was vivid green. He thought it would be cool to shoot it and stick it to the windows. The windows were high windows on the floor he was on. So he did, and instead, it just broke the window—shattered it completely. It was a $10,000 window.

But kids will be kids was kind of our point of view. What the hell. He didn't get in any trouble. That was the spirit of the place.

But it wasn't just Tony. There was a lot of playing going on, which is what made it fun. I think it's very good for them because they needed relief from the intense work they were doing. It was like a big playground, but they were very serious, focused people at the same time.

You could probably talk to everybody that was of the first hundred people that worked there, and they could all tell you a story about Tony or numerous different people, because they were just all a bunch of kids that liked to play. I kind of remember the story about the slime, but I don't remember it enough to speak about it.

People were there most of their lives, so they had to have some fun too. We used to do squirt gun fights out in the parking lot and play online games with each other. People had to blow off steam somehow.

Design

There were a couple of layers. Marc had seen all that, he had written it up, he had drawn it. It was there. But the other layers were more due to the specific individuals who worked there.

Bill and Andy's design aesthetic was all about ease of use and delighting the user. Between them and Susan Kare, who was responsible for the look and feel of the UI, it was about making something that would seem familiar and be fun and playful. It would make people not dread when their phone rang, but actually enjoy using it. That was the core design aesthetic.

The actual device was a lot clunkier and harder to use than that idea because we just couldn't do some of the things they wanted to do. But developing emoticons, a UI that looked like real objects that did what objects do when you touched them—you didn't need a manual to use it.

Andy wanted so badly to have something in the game room. When you clicked on the game room, something would come out. It was the flipping coin. He spent probably endless hours making that coin perfect, and he wanted people to have fun.

Marc would always say in meetings that we want it to be useful for people where they cannot live without it, but we also want it to be fun. We wanted the product to be very useful but also wanted it to interact and give people something to do when they're waiting for their flight or whatever.

The other layer—and this was something Andy and Bill learned at Apple—was that Scott Knaster, one of the first 10 hires, the technical writers who were going to document the machine, were there from the beginning. They were involved in every step of the design, every step of the coding. They knew it inside out. When they wrote the user documentation, it wasn't the usual junk that's hard to understand, but really good.

All those things put together helped make it the forerunner of what we have now. You pick an iPhone out of the box and just use it. You don't need to read anything or look anything up.

Perfectionism

They were of the mindset that they wanted it to be perfect when we shipped. That is the biggest lesson—it can't be perfect. No product is ever perfect. Even your iPhone or Android sometimes has issues.

They just spent too much time trying to make it perfect. In hindsight, it's easy to say what the mistakes were. You learn from those and try to apply it to your next project. But at the time, Marc was probably the one—he finally said, "I don't care where it's at, we're going to ship it." Because every time they would add something, it created a huge amount of bugs that would upset something else in the program. You add the flipping coin, but you don't know how that's going to affect other things, so you spend endless hours trying to get it all to work together.

That was the mistake—let's just do one thing and do it well, then make changes. But nobody knew that back then.

Again, greatest strengths, greatest weaknesses. We had a great time, and maybe we should have had a little less fun and been a little more focused. We didn't have to worry about money too often until the very end. We had enough money to do what we felt like as opposed to what the market demanded, and that's not a good idea.

We were trying to do it all in one jump rather than like the PalmPilot, the Newton, and even the first iteration of the iPod—all it did was play music. Then they were like, "Okay, now we know we can play music and do emails." It was iterative. We were just trying to do it all at once. We wanted it to be fun and useful.

Bill unfortunately we couldn't interview on camera because he was going through a lot. His wife was really ill. We're sorry we could never find the time to interview Bill. But he's in the same camp as Andy—they're such perfectionists that they wanted everything to be perfect. They kind of lost sight of managing their team. To me, the big lesson is that there has to be some structure. The structure can be changed along the line, doesn't mean it has to be set in stone, but there has to be some guidelines for people to know which direction they're going in and deliverables.

The Newton

When they announced the Newton at CES, it was like a lightning bolt that went through General Magic. People were in shock. In retrospect, it's one of those things where you go, "Why did we trust John Sculley?" I don't think he was maliciously doing it. I truly think he thought they were two different things. But we felt betrayed.

That took the air out of everybody's tires because you could see the writing on the wall. That was hard. We never recovered from that.

After that, the PalmPilot came out—which is not something we talk about in the film. I've always wondered why. I don't know if anybody talked about it and it didn't make the film, or if we didn't mention it. The PalmPilot was exactly what we were doing. They shipped. That was our mistake—we wanted it to be perfect. The PalmPilot worked, but it needed a lot of work. Once the Newton announcement and the PalmPilot came out, people within General Magic were like, "Okay, we're too late."

The Aftermath

Marc said after he left the company, he kind of disappeared for a couple of years because he lost his family, he lost his vision. That's pretty devastating. He wasn't able to follow through on what he promised his vision would be to the employees.

Bill and Andy, the same thing. It was really hard emotionally because they put literally blood, sweat, and tears into their work. They tried really hard. That combined with the Newton and PalmPilot coming out was very difficult. That's when it started imploding. Really emotionally hard on people.

There was a lot of joy involved as well as a lot of anxiety and pain. It was really fun. I had a great time.

Life After Magic

It was obvious to me that these people would go on to do great things. I'm sure it was obvious to Marc, Bill, and Andy too. I think Bill commented at one of our screenings that they knew someday some of these people would go on to create even better things than he and Bill had created.

These minds are so brilliant, it would have been unusual if they had not gone on to do great things. When I say great things, I mean things that change the world. There are a lot of people that do fun things, like make a game app that keeps us entertained but doesn't change the world. What the people at General Magic wanted to do was change the world with our device.

I always knew Tony was going to be crazy successful. Steve Perlman and Phil Goldman started WebTV together and went on to do other great things. It was obvious. We didn't know what, but they were too brilliant not to create something really terrific. It's just that generation—like there is now a generation of people that will go on to create something great. It's evolution.

The leadership skills and ethos of Marc, Bill, and Andy—they were incredibly good talent pickers. They really were. They just knew how to size people up and also how to get the best out of them. They encouraged the kids to keep striving. Marc was able to sell his vision to anybody who came anywhere near him. They were just really good at spotting and nurturing talent. That's what made it so special.

The Long View

I've worked for three people who founded companies after I left in 1995—three people from General Magic formed their own companies at different times, and I worked for each of them. Even though they were all from General Magic and we built great teams, it was never the same. It's hard to duplicate what we had at General Magic. People had truly a connection with each other. It was definitely very unique and exciting for the time.

Dee came out of HP HR, Hewlett-Packard HR. The old HP way, which is be decent to your employees—they're partners, not just assets to be exploited. She was absolutely instrumental and fundamental to the company's ability to recruit and nurture talent. It had a lot to do with her as well.

Lessons Learned

The deals were so complicated and the range of people we had to deal with at every level—from the supply chain through the National Security Agency. I learned how to build alliances and get these big companies to do things. It was an incredibly complicated legal environment. I learned a lot about how to do all that stuff. It was fun.

For me, in retrospect now, it's come full circle because I loved being there so much from 1990 to '95 and got to experience something very unique. Then watching all these people grow up—some of their kids are now going to college and getting married and will go on to do great things. To me, that is the most satisfying thing.

And then being involved with the movie and getting reconnected with everybody. It's been a wonderful experience of 28 years of being involved with General Magic. I've always said, long before the movie was even thought about, it was a company that changed my life and my career path. I think it probably changed the lives of 90% of the people who worked there. If they hadn't worked there, they would obviously be doing something very different.

Reflections

I think of it as a remarkable time in history for Silicon Valley. We knew we had something special with the group of people and what we were trying to do, but we didn't know exactly what it was and we didn't know it was way too early.

I loved every minute of it. I loved going to work every single day, even on the bad days. I truly loved being around those people. Every single one of them was brilliant—such positive, energetic, smart people. When I think of General Magic, I think of it as a whole. I'll think of things like pranks that Tony did or some of the talks that Marc would give that might be a little uncomfortable because we had to get serious. But I don't think of it as individual moments because all of it made General Magic what it was. That's what was really remarkable about it.

I'm so thankful to have been there. There are people there that I have lifelong connections with—I'm still very much involved in many of their lives and they're involved in mine. It was an incredible connection that will continue on. I loved every single minute of it.

I'm a movie producer now. I retired last year from law—I did that for 35 years, that was enough. We've got two movie projects in the hopper. We're going to keep going—I'm working with Matt and Sarah, the directors of the General Magic documentary. One's a contemporary political story and one is a fundamental women's issue story. It's not very glamorous, but it's a hell of a lot more fun than practicing law.